Commedia Dell’arte

A comprehensive overview of the Commedia dell’arte genre for teachers, students, and Enthusiasts.

Commedia dell’arte – a theatrical style that began to develop in Italy in the 16th century, which was characterized by the use of masks and the improvisation of the text according to a basic plot outline. Arte –arte literally means in Italian – ‘occupation’ or ‘craftsman’, meaning comedy performed by professional actors who worked in the theater for a living. The dallarte players (in Italian – ‘comici dell’arte’) were organized in bands that traveled and performed with great success all over Europe during the Renaissance.

Historical Overview

The Renaissance culture was characterized by a renewed interest in Greek and Roman art, and development of artistic forms inspired directly by the ancient classical patterns. This trend did not skip the field of theater. Universities established during that period began teaching ancient plays, and in particular Greek tragedies and Roman comedies by playwrights Plautus and Terence. These classical dramatic texts were often performed in Latin by amateur actors, primarily students of literature and philosophy. This theatrical style was known as “Commedia Erudita.” These performances were not open to the general public but were typically performed in front of upper-class audiences in universities, noble courts, or scholarly circles.

The Commedia dell’arte folk troupes, which began to emerge in Italy in the early 16th century, “inherited” the subversive aspect of traditional Roman comedy. Pinpointing precisely when and how Commedia dell’arte was born has proven challenging. The prevalent assumption being that it began with troupes of mostly street performers, which were popular in markets and city squares during the medieval period: jesters, pantomimes, buffoons, jugglers, magicians, dancers and wandering singers (troubadours). They engaged in storytelling, singing, and music, presenting stories and plots focusing on love, heroism, and witchcraft. Organizing in troupes, refining performance skills using familiar classical dramatic patterns, led to the development of a new theatrical form. This form enabled troupes to earn a living from their performances, marking a significant historical shift in the evolution of theater. From the days of ancient Greece and up until that moment in time, actors were merely amateurs whose main income did not come solely from theater.

The Commedia dell’arte troupes

In Commedia dell’arte, the actors were professionals who lived and earned their livelihoods through their art. The commedia troupes lived and performed together, traveling from city to village and from country to country, performing in markets and town squares, and making a living from their simple, sometimes crude plays that were full of life, humor, and freshness. The troupes fostered a unique way of life; relationships of mutual dependence—professional, economic, and emotional—were formed among the actors, making the troupes function like extended families. Since they relied solely on their art, they generally did not enjoy financial security. Their communal lifestyle and renunciation of stable, comfortable lives turned these troupes into a model of total dedication to creative work for later generations. From the second half of the 16th century until the beginning of the 17th century, commedia dell’arte became very popular. Italian troupes were invited to perform throughout Europe. The golden age of commedia dell’arte was in France at the beginning of the 17th century, where Italian troupes became sought-after and popular in aristocratic and royal circles, even receiving funding and a permanent place at these courts. In hindsight, this success was also a factor in the genre’s decline—the troupes, accustomed to performing for ordinary people and improvising without censorship or restrictions, were now subjected to the demands of their ‘funding’ hosts, who wanted to refine the performances, control the repertoire, the characters in the play, and sometimes even the identity of the actors. These constraints ultimately stifled, damaged, and effectively stunted the free spirit and fresh vitality of commedia dell’arte.

The Characteristics of Commedia dell’arte

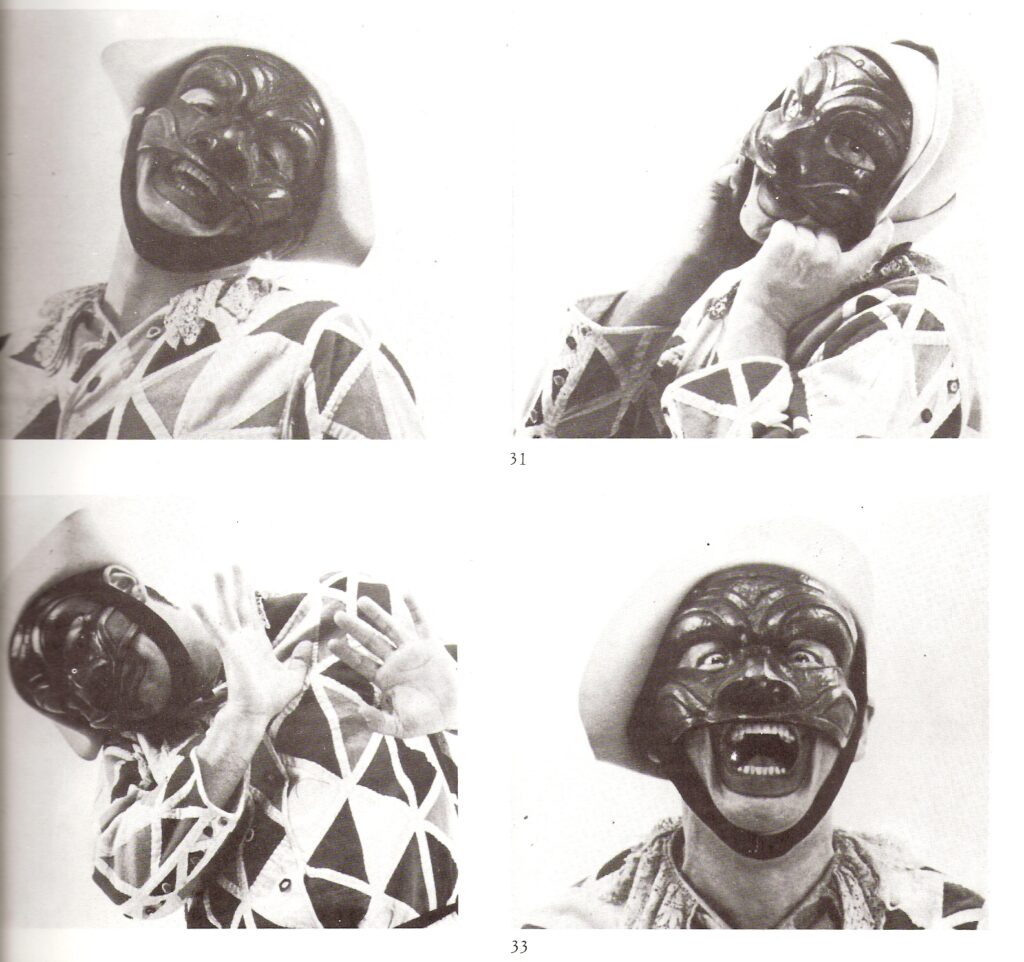

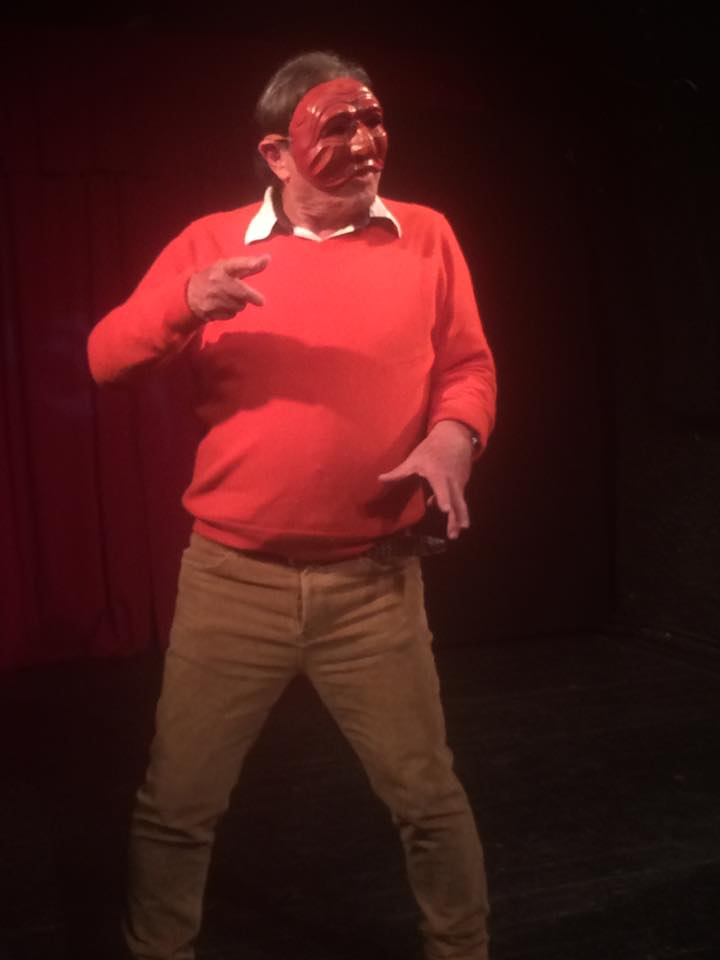

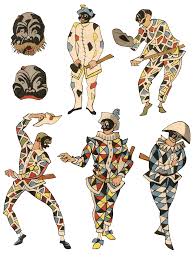

Fixed Characters Commedia dell’arte shows were based on a set repertoire of archetypal characters characterized by typical costumes and masks that allowed the audience to easily identify each character, reviving the ancient theater tradition of actors donning tragic or comic masks. Many characters in Commedia dell’arte were the ‘reincarnation’ of archetypal characters from Greek and Roman comedies, or, in fact, the embodiment of one or more human weaknesses.

The use of masks refined the stereotypical design of the characters. As mentioned earlier, Commedia dell’arte revived characters from Greek and Roman comedies but gave them a modern twist: their attire and costumes reflected characters typical of 16th-century European society. For instance, the character of ‘The Old Man’ from classical comedies reappeared in Commedia dell’arte as ‘Pantalone,’ and the character of the ‘Braggart Soldier’ re-emerged as ‘Capitano,’ a military man wearing fancy clothes, boasting tales of heroism, but at the moment of truth, reveals himself as a coward. The scheming servant characters from Roman comedy have also found new life in various versions in Commedia dell’arte. Most famous of them all is Harlequin, a well-meaning and clever servant, who gets what he wants – and what his master needs – with shrewd practicality and wit. He’s pragmatic and quick on his feet, ignorant yet sharp, who can improvise his way into and out of every situation. It is no surprise, therefore, that Harlequin’s character became so immensely popular, as he represents of the common man with down-to-earth wisdom, struggling for his daily existence. Harlequin’s character underwent numerous adaptations and variations, such as Scapin in Molière’s “Scapin the Schemer” (Les Fourberies de Scapin) and Truffaldino in Goldoni’s “The Servant of Two Masters”. Even the character of Charlie Chaplin’s tramp, may be considered a modern adaptation of Harlequin, who, more than any other character, embodies the free-spirited and mischievous essence of Commedia dell’arte.

In various troupes, each actor specialized in portraying one specific character – one specific mask throughout their career. This specialization allowed them to master and develop extraordinary, virtuosic theatrical skills. Their vast experience enabled Commedia dell’arte actors to revolutionize the world of theater with an innovative theatrical tool for the time – improvisation. For the first time in theater history, a show didn’t rely on a play or written text, instead they used the ‘scenario’ (a basic plot structure) and the dell’arte troupe’s improvisational skills.

The Actor’s Skills As mentioned, each Commedia dell’arte actor specialized in portraying one particular character, which he spent his entire professional life perfecting. This specialization enabled them to fully embody the character and made improvising and finding its place in the scenario immeasurably easier. Each actor developed a rich repertoire of comedic verbal and physical maneuvers that characterized the specific character in various possible situations: moments of anger, courtship, parental-child conflicts, banter, and other witty-isms delivered with ‘spontaneity’. The Commedia dell’arte actors’ skill lay in unhesitatingly finding suitable actions and words and expressing them naturally on the spot. Over the years, an oral tradition emerged, with actors armed with pre-prepared jokes, monologues, and songs. This can be likened to a modern-day stand-up comedian who arrives at a show equipped with a supply of ready-made jokes and stories, which they can choose and integrate spontaneously between new performance bits. Commedia dell’arte actors were required to sing, play music, and move freely, and their performances were rich in physical humor, acrobatics, slapstick, dancing, and live music played by the actors themselves.

Another historical innovation was the integration of actresses into the shows. Women were not allowed to act in the theater from ancient Greece to the Renaissance. The change was brought about by the “Gelosi” troupe, the most famous Commedia dell’arte troupe. The troupe was led by the actors Francesco Andreini and Isabella Canali from 1583 to 1604. Canali, a respected poetess in her time, was the creative force leading the troupe. Legend has it that during one performance, when the actor playing the role of the young female lover fell ill, Isabella, familiar with the troupe’s entire repertoire, replaced him and achieved great success. She became known as an enchanting actress with an uncanny stage presence. After she passed away in 1604. the troupe disbanded. However, Canali’s character continued to serve as a source of inspiration, encouraging other troupes to involve women in the role of the young female lover (and so, over the years, the young lovers’ characters began to be played without masks). Isabella’s name became the basis for the archetype of the young female lover that was added to the gallery of fixed Commedia dell’arte characters.

Improvisation Commedia dell’arte was based on improvisation: the actors did not present a written play but improvised the text during the show itself. They relied on the scenario – a general pre-prepared plot (either by the head of the troupe, one of the actors, or some other writer) that outlined the main events and major turning points but left the creation of dialogue to the actors on stage. Therefore, Commedia dell’arte actors were not only performing artists but also creative artists: they had to improvise perfectly in front of the audience and recreate familiar scenes in real-time, providing the performance with a fresh and authentic quality. The integration of improvisation into fixed patterns and familiar elements gave Commedia dell’arte its distinctive essence – a unique blend of free spirit and strict professional discipline. It was spontaneous, brilliantly original, witty, relevant, and at times satirical.

The Lazzi Throughout the scenario, were non-verbal comic interludes: pantomime, acrobatic tricks, juggling, and more. These segments, known as “lazzi,” were not necessarily connected to the plot. Sometimes, they were used to ‘reinvigorate’ the audience. They were designed to amuse, entertain, and wow the spectators with the actors’ virtuosity. The “lazzi” were usually performed by the more common characters and allowed the actors to form a connection with the audience – yet another characteristic of Commedia dell’arte that made its way to modern-day circus shows and stand-up comedy. This contrasted with neo-classical and the realistic theater that followed, which maintained an absolute separation between the stage and the audience (the well-known “fourth wall” convention). Part of the popularity of Commedia dell’arte stemmed from this direct and immediate connection with the audience.

From Then Until Now

Commedia dell’arte reached its peak in the early 17th century, particularly in France. Troupes of Commedia dell’arte performers traveled to almost every European country, also leaving their mark on literature and the art of painting. They became an integral part of French theater, and even had a profound influencing on aristocratic neo-classical theater. This influence was noticeable, among others, in the works of Goldoni, Molière, and Shakespeare. These playwrights extensively used characters and basic plot structures from Commedia dell’arte in their plays. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Italian troupes began to establish themselves within the French courts of kings and nobles. It is within these settings that Commedia dell’arte started to devolve – patrons demanded refinement in language, costume design, and, at times, in content and style. The once rugged, spontaneous, folksy and free-spirited art of Commedia dell’arte that allowed its actors creative freedom gradually transformed into carefully rehearsed and structured reenactments of the achievements of previous actor generations.

During this period, when most troupes settled in one court or another and rarely traveled, a style of wandering puppet theater emerged, adapting elements of Commedia dell’arte – from actors in masks to masked puppets, maintaining the same classic plot structure. This form of theater, operated by one or two puppeteers, also gained considerable success in rural areas and markets across Europe. In England, a style of puppet theater featuring two characters – Punch and Judy – developed and remains successful to this day, drawing inspiration from the Commedia dell’arte characters Pulcinella and Columbina.

In the mid-19th century, a renewed interest in Commedia dell’arte arose – this time from romantic writers captivated by the tales of the wandering troupes. They perceived Commedia dell’arte actors as emblematic of free and rebellious artists dedicated entirely to their craft. Théophile Gautier’s novel “Captain Fracasse,” published in 1863 (later adapted into a 1990 film of the same name directed by Ettore Scola), epitomizes this romantic perspective: the alliance between an impoverished aristocrat and a troupe of wandering actors symbolizes the rejection of comfortable bourgeois life in favor of the free and spiritual life of an artist.

In the early 20th century, innovative thinkers and creators in the field of theater began to explore Commedia dell’arte from a different angle: they did not seek it as a source of inspiration for adventure stories or romantic rebellion but as a model for future theater. These innovators were searching for an alternative to the dominant realistic style that prevailed in Western theater from the late 19th century onward. The birth of cinema – a competing medium with a clear realistic potential – reinforced the need to redefine the uniqueness of theatrical language. Artists and creators such as the British Gordon Craig from England, Vsevolod Meyerhold from Russia, Max Reinhardt from Germany, and Jacques Copeau from France delved into the history of theater in search of historical models as sources of inspiration. For these artists, Commedia dell’arte served as a valuable model for sophisticated, anti-realistic theater. The use of masks, for example, symbolized, in the eyes of these theater practitioners, the true power of theater – a medium that, despite its apparent artificiality, can touch the truth.

In Realistic Theater, the written play is a central component. Other elements, such as stage design, music, costumes, and even the actors’ movements on stage, are often seen as secondary components, subject to the verbal text and serving it. 20th century theater innovators challenged this perception, viewing it as a “literary” approach that diminishes stage language. The uniqueness of theater, they emphasized, lies in the integration of the various theatrical elements, with the text being merely one of them. Commedia dell’arte, which relied on virtuosic physical language and visually captivating gestures, demonstrated the possibility of such a theater’s existence. Furthermore, it provided a model for improvisational theater. One of the challenges facing actors is to breathe life into the text written by the playwright so that it appears as an authentic expression of their experience at a given moment, rather than a rehearsed recitation. Inspired by models such as Commedia dell’arte, theater creators in the 20th century developed working methods aimed at restoring the experiential freshness of theater.

The influence of Commedia dell’arte in the 20th century is particularly noticeable in Italy, with the works of playwrights and directors such as Luigi Pirandello, Eduardo De Filippo, Dario Fo, and Giorgio Strehler. An especially well-known example is the 1947 production, directed by Strehler, of Goldoni’s play “The Servant of Two Masters.” This show, staged in the style of Commedia dell’arte, became a modern theater classic, gracing the stage for over 50 years.

Commedia dell’arte in Israeli Theater

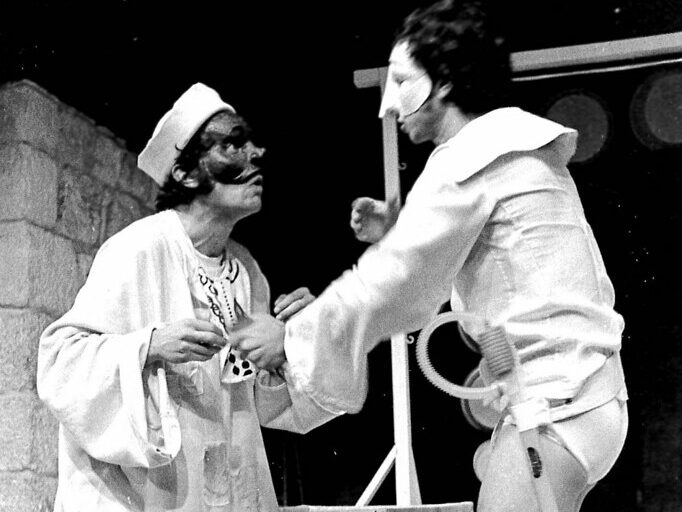

The Servant of Two Masters – Khan Theater JerusalemThe first professional production in the Commedia dell’arte style staged in Israel was “The Servant of Two Masters” directed by Michael Alfreds. It premiered at the Khan Theater in Jerusalem in 1974. The show ran for three seasons, becoming the flagship production of the Khan Theater, featuring prominent actors such as Seffi Rivlin, Sasson Gabai, Shifra Milstein, Uri Avrahami, Avi Pnini, Shlomo Tarshish, and more. and ran for three consecutive seasons success of the play was attributed to the actors’ excellent improvisational skills. Alfreds worked with the actors on a basic action menu, allowing them to improvise different scenarios every evening without pre-planning. The show was born anew each time, as the actors gave it their all, infusing it with maximum liveliness and vitality. Alfreds skillfully merged the spirit of Commedia dell’arte with the unique atmosphere of Jerusalem’s Khan Theater, choosing to open the performance at the theater’s gates. Actors Uri Avrahami and Shlomo Tarshish welcomed and engaged with the audience, ‘warming them up’ before entering the theater hall. Excerpts from the play were also performed in various city streets before diverse audiences. The show’s music and songs, collected and adapted by Hana Hacohen, were based on original material from the Renaissance and early nineteenth-century period.

“Michael Alfreds has absolute control over this theatrical material. He is familiar with every single detail and knows precisely what he wants to achieve on stage. The result is calculated and precise like clockwork: the onstage wild behavior, jumps, antics, and acrobatics, which sometimes seem completely spontaneous. Michael Alfreds allows his actors total freedom and, at the same time, demands a perfectly disciplined performance from them, vital for the virtuosic performance of the characters without which they have no ‘raison d’etre.’ The incredibly meticulous and thorough work with a young, sometimes inexperienced ensemble yields excellent results…” (Idit Zartal, “Acting Exercises,” Davar newspaper, 28.11.74)

The Golden Goose – Yoram Boker Theater In 1990, as part of the Israel Festival, “The Golden Goose” was staged in the Commedia dell’arte style by the Yoram Boker Theater, directed by Yoram Boker himself. The ensemble included Uri Tenenbaum, Ezra Dagan, Irit Ben Tzur, and Effi Amir.

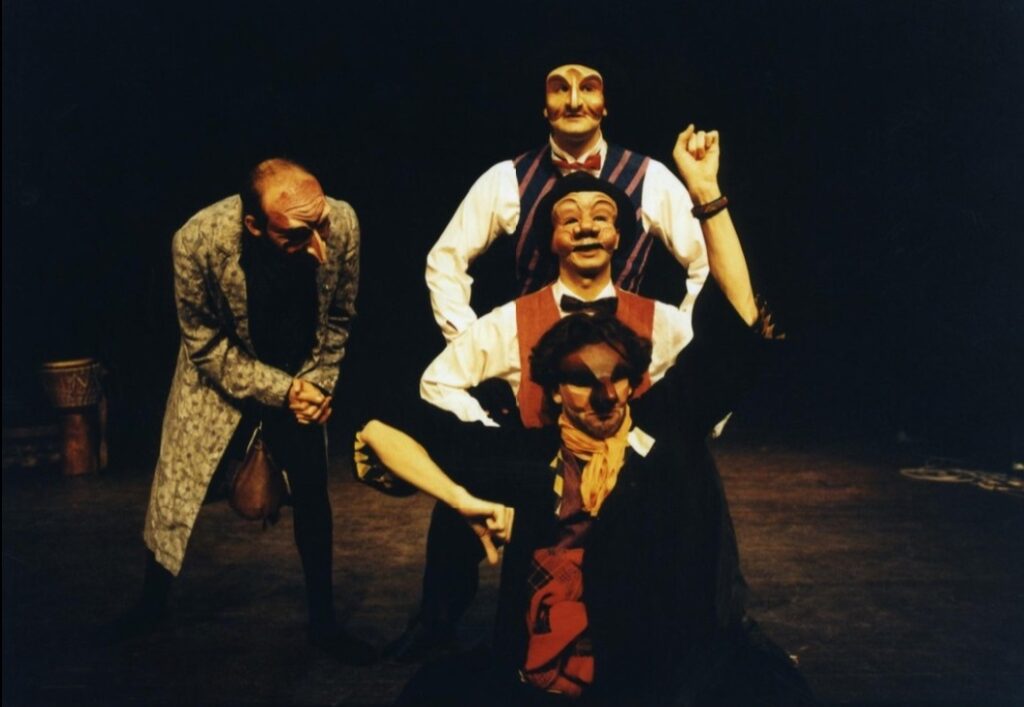

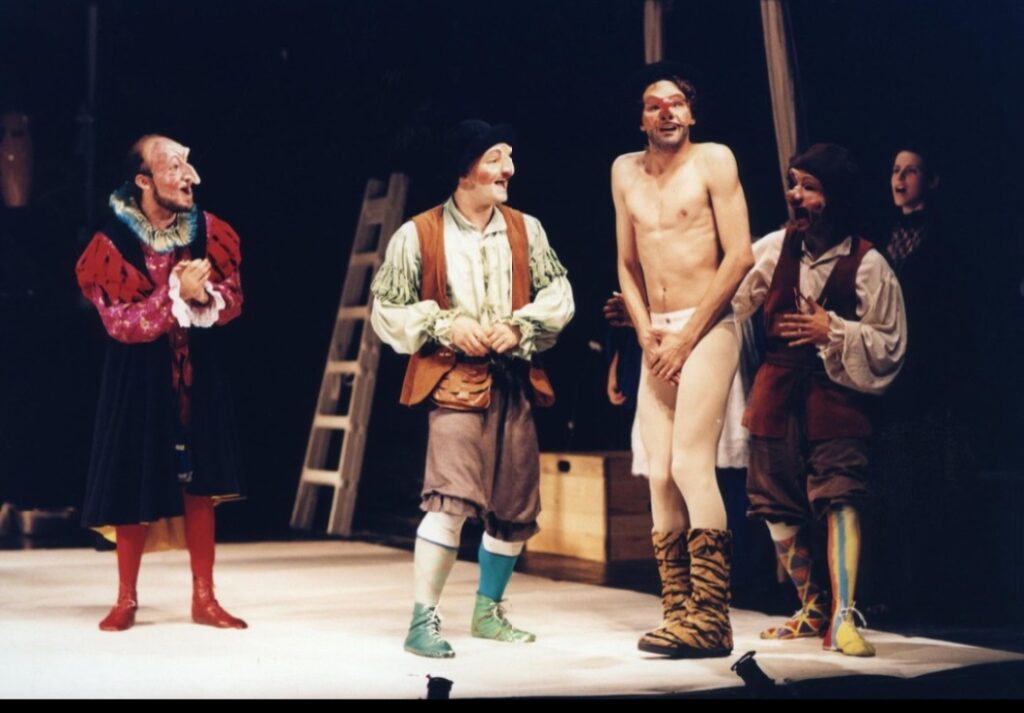

Mandragola – Habima Theater In 1996, the Habima Theater presented “Mandragola,” directed by Ilan Ronen and performed by the young Habima Theater ensemble, including Guy Loel, Sigalit Fuchs, Yossi Eini, Amnon Fisher, Guy Messika, and others. The production was the first by the HaBima Youth theater group, performed about 210 times, and achieved great success.

Documentation of the play: Part A, Part B.

“Ilan Ronen built ‘Mandragola’ as a play within a play. The actors play a troupe that presents the humorous story of lustful Calinco, the beautiful and chaste Lucretia, and her old and foolish husband. In this style, actors are supposed to fulfill a dual role. However, with Ronen, the ensemble has no specific characteristic or defined style, and when the actors step out of character, they are simply themselves. This allows them to amuse the audience with an abundance of imaginative and humorous stage inventions. The general merriment is enhanced by Miki Ben-Knaan’s elaborate set and costume design, Yehudit Grinspan’s masks, and Ori Vidislavski’s music. This is Habima’s young ensemble’s premiere performance, and they certainly know how to have fun, they enjoy being on stage, and invest a great deal of effort to share their enjoyment with the audience—and most of the time, they succeed.”

(Shosh Veitz, “Yediot Ahronot,” 5.2.1997)

Psik Theater Founded in 1997 in Jerusalem, Psik Theater was established by graduates of Nissan Nativ Acting Studio: Assi Shimoni, Shmuel Hadgas, and Uzi Biton. In its early years, the group focused on practical exploration of Commedia dell’arte. During this period, the ensemble collaborated with theater masters worldwide, including Pierre Tobiana and Dussio Bellugi (Théâtre du Soleil, France), and Adriano Urosevich, head of the Commedia dell’arte school in Venice. For years, the group maintained a collaborative lifestyle, reminiscent of ancient comedy troupes, and performed extensively in streets and markets, engaging with diverse audiences and redefining the actor-audience relationship. During this time, Psik Theater created numerous works that broke the boundaries between the audience and the stage, as well as time and site-specific productions.

Later, the theater delved into the study of masks, the design of Israeli mask characters, exploring the structures of Commedia dell’arte scenarios, and pushing the limits of these structures into the framework of modern-day plays. The fruits of this work include group creations such as “An Israeli Masks Project,” “The Twins,” and “The Jerusalem Comedy.” Through these three productions, Psik Theater established a new and unique genre, defining it as Israeli Commedia dell’arte. As the theater evolved and settled in Jerusalem, it shifted towards developing works based on young, experimental Israeli plays, moving from the stylized Commedia dell’arte to realistic productions sans masks, incorporating socio-historical themes of the State of Israel and the Jewish people.

Over the years, various theaters have staged different productions using Commedia dell’arte masks, usually in a play-within-a-play format. Examples include “Isabella” directed by Yael Ronen at the Jerusalem Theater in 2006, “Mandragola” at the Beit Lessin Theater in 2011, “Wing 6” directed by Yafim Kutcher at the Simta Theater in 2011, and more. Additionally, Commedia dell’arte-style productions have been performed in schools by leading teachers in the field, such as Avraham Dana, Zvika Fishzon, Gennady Babitzky, Yafim Kutcher, Nelly Amar, Haim Abud, and others.

Professor Yoram Boker, who taught for four decades at acting schools such as Tel Aviv University, Beit Zvi, and Seminar Hakibbutzim College, trained generations of actors in the art of Commedia dell’arte. The method taught by Yoram Boker in Israel was influenced by the French school, which was characterized, among other things, by the refinement of characters and the role reversal between Arlecchino and Brighella. In the Italian school, Brighella was the leading zanni (comic servant)—clever and cunning, in contrast to the innocent Arlecchino. In Yoram Boker’s approach, Arlecchino became the primary zanni—clever and cunning, while Brighella became the naive servant. The mask for Brighella in Israel was also different from the classic Italian design, becoming more rounded with an open expression, rather than the stern look typical of the Italian version. Another change Boker introduced among his students, unique to Israel, was the use of masks for the young lover characters. In Italy, with the genre’s development during the Renaissance and the casting of women in the role of the beloved (at first, women were forbidden from acting in theater, and men filled these roles), the masks were removed from these characters. To this day, around the world, the lover roles are performed without masks.

Graduates, mainly from Tel Aviv University, formed groups under his guidance, creating and producing independent Commedia dell’arte-style shows within the sphere of independent theater—a phenomenon defined as “fringe” in the previous millennium.

The Man Who Married a Mute Woman – An Independent Production In 2000, a group of Yoram Boker’s graduates from Tel Aviv University, mounted “The Man Who Married a Mute Woman” at Tel Aviv’s Tmuna Theater. The show, directed by Yoram Boker in the Commedia dell’arte style, and featuring Ronen Hershkovitz, Nili Itzhaki-Gefen, Ofri Aloni, Anat Eliyahu, and Haim Abud, began as the group’s acting studies’ production project and continued successfully as an independent production at the Tmuna Theater upon their graduation.

My Wife’s Revenge – An Independent Production In 2003, right after completing their studies, another group of Tel Aviv University graduates began working with Yoram Boker – ‘Ensemble Cremeschnitte.’ The members of the ensemble – Hila Gonen, Barak Gonen, Sheffi Malek, Eyal Zusman, and Haim Abud – independently wrote, performed, and produced “My Wife’s Revenge”. The show, directed by Yoram Boker, premiered in 2004. The show gained success nationwide, regularly performing at the ZOA House, which, at the time, was considered a fringe theater center.

“There is much more to the show than just entertainment. Firstly, there is a very dedicated and talented ensemble of actors who, under the delicate direction of Yoram Boker, excels in creating strong and well-crafted characters. All in all, this is one of the most refreshing shows seen on our stages lately. Rush to the theater!!!” Lilach Dekel, Habama website, 5.12.04

Commotion on Stage – An Independent Production In 2007, yet another group of Tel Aviv University graduates – Shiri Elraz, Ronen Hershkovitz, Haim Abud, Liat Ophir Kislovich, and Hadas Kreidelman, created the play “Commotion on Stage” under Yoram Boker’s guidance. The play was performed at the Haifa International Children’s and Youth Theater Festival. The show was a huge success at the festival and won numerous awards: Directing Award – Yoram Boker and Elinor Keinan; Best Play Award – Members of the ensemble; Costume Design Award – Meirav Nathaniel Danon: Lighting Design Award – Meir Alon; Best Music Award – Misha Segal. At the end of the festival, the show was adopted by the Haifa Theater, but the theater was facing financial and managerial difficulties at the time, which led to a freeze in its activity, a change in management and in repertoire. The show did not continue to run.

“This was the most professional play at the festival. Professor Yoram Boker does what he knows best: fast-paced and stylized Commedia dell’arte. With his students, he put on a professional and dynamic performance… Boker manages to combine the stories and characters, and makes his own variations on the theatrical conventions: he turns the rich and stingy Pantalone into the wicked Mrs. Pantalone, and pairs Bernard Shaw’s Androcles with Harlequin, the resourceful servant of the Renaissance. Boker guides his actors well. Especially during the “stage fights” and comic antics, of which the show is full, so that the commotion is well-orchestrated and often looks like a stylized dance. In this sense, “Commotion” sets a high theatrical standard of restrained stage ethos, which deviates in the best possible way from the wildness, not to say vulgarity, common in many children and youth shows, where the commotion on stage is almost a necessary stamp of approval.” Haim Nagid, HaBama website, 7.4.07

“Happiness personified! Our personal bet for the lucky winner of the competition! Professor Yoram Boker, known as a masterful mime, and director Elinor Keinan, have recruited a collection of insanely talented actors for the play. With amazing precision and accuracy, the actors manage to portray the oh-so-stereotypical and familiar characters of Pantalone (this time as a woman), Harlequin, the lovers and the captain. The set design, in an impressive duet with the lighting, allows the audience to focus on the actors’ bodies and faces, as well as the transition from city to nature, and even the changes it goes through: at times it is a bed for the lovers and at others, a dangerous trap. Towards the end of the play, the audience, who have been sitting on the edge of their seats for nearly an hour, are rolling with laughter, shouting at the actors and applauding the wonderful and very deserving cast!” Rachel Elg’im, Haaretz, 5.4.07

In 2010, the Scapino Theater Company was founded by Ella Gopher, Barak Gonen and Haim Abud. The latter two are former students of Yoram Boker and members of the ‘Cremeschnitte Ensemble’ and Ella Gopher – a student of Haim Abud. The company is dedicated to the preservation, development and creation of mask theater art in general and Commedia dell’arte in particular. Their first production was “The Miser: Now What?” which premiered in 2011 and continues to be performed to this day, with over 500 shows across the country and even abroad, a notable achievement for an independently running play. Ela Gopher won the Golden Hedgehog Award in 2012 for her performance in the play, and in 2019, the play was adapted and translated into Arabic and performed by the Nazareth Fringe Center Ensemble, directed by Chaim Avod. In 2014, Orit Peres, a student of Haim Abud, joined the company. The four of them form the core of the company, in addition to the company’s set, costume and mask designers – who have worked with the company members in various frameworks since the early 2000s. The ensemble continued to specialize and create numerous Commedia dell’arte productions and add new actors and actresses to its ranks. Its veteran members began teaching in professional acting schools, thus distinguishing and training a new generation of Commedia dell’arte actors. The ensemble is active in the international Commedia dell’arte scene and is a member of the international SAT organization, which unites Commedia dell’arte artists, creators and researchers. With the organization’s support, the ensemble initiated and produced the events of the International Commedia dell’arte Day in Israel, hosting international workshops and masterclasses. Taking advantage of the COVID-19 period, the organization collaborated on international online productions, solidifying its position as one of the leading dell’arte troupes worldwide. In 2020, it was recognized as a theater group and began receiving support from the Israeli Ministry of Culture.

International Commedia dell’arte Day

Background

On February 25th, the ‘International Commedia dell’arte Day’ was established by UNESCO, the United Nations organization for education, science, and culture. The special day aims to promote and expand knowledge about this unique theater language that originated in Italy during the Renaissance and continues to thrive, kick, and perform globally to this day. Supported by UNESCO and the Italian Center of the Theatre Institute ITI International, the day is celebrated in numerous countries around the world. Events take place in universities, theaters, drama schools, cultural centers, museums, and include lectures, workshops, exhibitions, masterclasses, performances, and other events by a large community that considers itself as part of the long tradition of Commedia dell’arte. All of this serves as a living testimony that this distinctive style, the cradle of modern theater, remains lively, fresh, and kicking.

This special day of celebration is an initiative of the SAT organization, an international organization dedicated to the study, development, and preservation of Commedia dell’arte heritage. Comprising artists, researchers, and fine arts professionals, SAT is recognized by UNESCO as an organization dealing with undocumented cultural heritage of unique value. This collaboration led to the establishment of the International Commedia dell’arte Day in 2010, celebrated annually on February 25th. On this date in 1545, the official founding document of ‘Compagnia dei Gelosi’ (“Company of Jealous Ones”) was signed, marking the earliest recorded organization of Commedia dell’arte actors as a professional troupe. Thus, officially, Commedia dell’arte was born and began spreading from the squares of Italian towns and villages to the noble courtyards, eventually reaching all of Europe.

The founding agreement of the “Compagnia dei Gelosi”

The Members of the Comedies

February 25, 1545, Announcement 3, Wednesday, in Padua, on San Leonardi Street; at my home, the notary’s house, in the ground-floor room.

Since the members listed below—namely, the gentlemen Maffeo, known as Zanino of Padua, Vincenzo of Venice, Francesco of Lira, Hieronymus of San Luca, Zoandomengo known as Rizzo, Zoana of Treviso, Tofano of Bastia, and Francesco Moschian—wish to establish a “Brothers’ Company” that will last until the first day of Lent of the following year, 1546, and begin during the eight days of the upcoming Easter holiday, they have agreed and decided together that, for this company to exist in brotherly love until the mentioned date, without hatred, resentment, or dissolution, they shall lovingly uphold and maintain, as befits good and loyal friends, all the clauses recorded here. They indeed promise to observe them without objection; otherwise, they will be penalized and pay a fine as specified here.

First of all, they have unanimously chosen the aforementioned Master Maffeo to be their leader in the performance of comedies wherever they may find themselves, and all the above members shall obey him in all matters related to their duty to perform the aforementioned comedies. They shall go and improvise in the places he directs.

Furthermore, if one of the troupe members falls ill during the mentioned period, that member will be cared for and supported with the funds the troupe has earned jointly, and he will be hospitalized (from these funds) until he recovers, or escorted home; during that time, he shall receive his share, but from the moment he is brought home, he will receive nothing further from the said company.

If the company is invited to travel to other places, they must go, and the arrangements for this will be handled by the aforementioned Zanino.

Furthermore, for this company to survive in love until the said date, the above members have agreed to create a strongbox with three secure keys: one will be held by the aforementioned head (of the troupe), another by Francesco of Lira, and the third by Vincenzo of Venice. Into this box, they must deposit, each day they earn income, sometimes a ducat, sometimes more or less, depending on the income. This box shall never be opened, nor shall any money be taken from it, without the explicit approval and agreement of all members. If, during the company’s existence, any member, or two or more members, consider leaving and abandoning the others to their disgrace and harm, then those who leave, aside from the penalties recorded here, shall lose all benefit and rights to the money within the aforementioned box, and the departing members’ share will be divided equally among the members who remain united in the brotherly bond and do not break from the company.

If any member leaves the company, they will not only lose their share of the money in the box, but they will also be liable to pay a sum of one hundred lire, divided as follows: a portion to the local authorities, a portion to the poor, and a portion to the company. These allocations shall be determined, mentioned, and enforced wherever the troupe members find it appropriate.

Furthermore, it was decided to acquire a horse, at common expense, to carry the belongings of the brothers (the troupe members) from place to place.

It was also decided that when the troupe arrives in Padua, expected in June, the money in the box shall be distributed.

It was further decided that at the beginning of the upcoming September, the troupe shall, by general agreement, embark on a journey, and its members shall not be subject to the aforementioned penalty.

Finally, it was decided that the above members shall not gamble among themselves with cards or other games, except when wagering food.

International Del’Arte Comedy Day in Israel

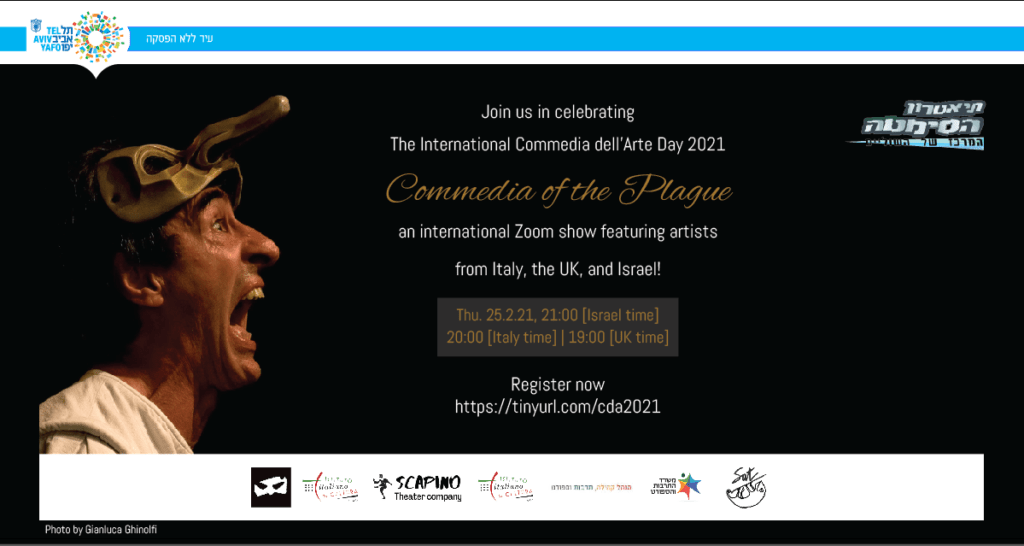

In Israel, the day was first celebrated in 2014, initiated by the Scapino Ensemble, representing Israel in the SAT organization, in collaboration with Hasimta Theatre and sponsored by the Italian Cultural Institute. The event included a masterclass for actors led by Prof. Yoram Boker, an exhibition by mask artist Yehudit Grinspan, a professional panel, and a Commedia dell’arte show. Since then, the day has been marked annually throughout the country, hosting leading Italian dell’arte artists such as Cristina Coltelli, Fabrizio Paladin, Fabio Mangolini, and others. In 2021, due to the pandemic, quarantines and venue closures, Scapino Ensemble organized an international online event, Commedia of the Plague, featuring dell’arte artists from around the world performing monologues related to the pandemic. Video of the show >

Events in Israel are produced by the Scapino Ensemble, in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute in Tel Aviv and Haifa, under the artistic direction of Haim Abud.

2014

The inaugural events took place at the Hasimta Theatre and included an Italian-style festive reception graced by the presence of the head of the Italian Institute, a masterclass for actors led by Prof. Yoram Boker, an exhibition of Commedia dell’arte masks by artist Yehudit Grinspan, a ‘To Be or not to Be with a Mask’ panel discussion with Prof. Yoram Boker, Avraham Dana, Irit Frank, Haim Abud and Ronen Hershkovitz, and a performance of “The Miser, What Now?” by the Scapino Ensemble.

The event was initiated by the Scapino Ensemble | Artistic director: Haim Abud | Produced by: Hasimta Theater | Sponsored by the Italian Institute, Tel Aviv.

Additional photos: Yoram Boker Masterclass Yehudit Grinspan Mask Exhibition Opening Ceremony

2015

Events were held at the Hasimta Theater, featuring an Italian-style reception graced by the presence of the head of the Italian Cultural Institute, a children’s show “Comedy in Masks” by the Scapino Ensemble, a panel discussion, and a Commedia dell’arte performance of “Harlequin and the Three Cuckolds” directed by Ofira Laniado.

The event was initiated by the Scapino Ensemble | Artistic director: Haim Abud | Produced by: Hasimta Theater | Sponsored by the Italian Institute, Tel Aviv.

2016

This year’s events spanned two days, In honor of today’s events, Fabrizio Palladino arrived in Israel from Italy—a actor, director, musician, playwright, and mask creator. Fabrizio is considered one of the leading contemporary Commedia dell’arte artists in the world and held a master class for actors at the Holon Puppet Theater Center. He also presented a Commedia dell’arte play titled “The Exhausting Affairs of Love,” directed and performed by Fabrizio Palladino and actress Joanna Saraiva. Additionally, an exhibition of illustrations titled “Arlecchino and Friends,” courtesy of the Israeli Illustrators Association, was featured, along with “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly,” a tribute to Ennio Morricone—the legendary film musician who passed away this year. There was also a live performance with Shlomi Goldberg and his band, and of course, “The Miser: Where to?” by the Scapino theater troupe.

The events in Israel were produced by the Scapino Ensemble, in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute in Tel Aviv and Haifa, under the artistic direction of Haim Abud.

2017

In this year marked 300 (!!!) performances of “The Miser, Now What?” , and to honor the festive show, famed actor Gabi Amrani joined in to perform scenes specially written for the evening. The evening began with Prof. Yoram Boker’s lecture on Commedia dell’arte, followed by, as always, an Italian-style reception graced by the presence of the head of the Italian Institute in Tel Aviv.

The events in Israel were produced by the Scapino Ensemble, in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute in Tel Aviv and Haifa, under the artistic direction of Haim Abud.

2018

Events to mark the day spread over a week from the north to the south of Israel – Beit Gabriel on the banks of the Sea of Galilee, Hasimta Theater in Tel Aviv, the Holon Puppet Theatre, and the Goodman Acting School in Be’er Sheva. This year featured a visit from the world-leading Commedia dell’arte artist, Cristina Coltelli. Aside from the traditional reception graced by the presence of the head of the Italian Institute in Tel Aviv, activities at Hasimta Theater also included the show “Harlequin’s Secrets,” conceived and performed by Cristina Coltelli and Marcella Colaianni. Further in the Hasimta Theatre, there was a morning family activity that included the performance “The Other-Siders” by the Scapino Ensemble, a mask workshop for children, and a mask-making workshop. Cristina conducted workshops, including a 4-day intensive workshop at the Holon Puppet Theatre Center for actors and artists in the field. She also led a workshop for students at the Goodman Acting School in Be’er Sheva. Cristina performed her show at Beit Gabriel and at the Be’er Sheva Fringe Center.

The events in Israel were produced by the Scapino Ensemble, in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute in Tel Aviv and Haifa, under the artistic direction of Haim Abud.

2019

This year, renowned Commedia dell’arte artist Fabio Mangolini was invited to perform his one-man show, “The Fly’s Lazzo.” Fabio performed in Beit Gabriel, ‘The Studio’ Theater in Haifa, and, of course, at Hasimta Theatre, including the traditional reception graced by the presence of the head of the Italian Institute in Tel Aviv.

The events in Israel were produced by the Scapino Ensemble, in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute in Tel Aviv and Haifa, under the artistic direction of Haim Abud.

2020

This year hosted mask designer and Commedia dell’arte actor Carlo de la Costa, who conducted mask-making workshops at the Holon Puppet Theatre and the Kukia Theater’s Performing Arts School in Rosh Pina. Carlo also gave an acting workshop at Zigota – Clore Center in Kfar Blum. Aside from the traditional reception, the central event at Hasimta Theater featured Carlo’s lecture and the world premiere of “A Minister’s Honor” produced by the Scapino Ensemble.

2021

Due to the pandemic, cultural events were halted worldwide. And so, to mark the International Commedia dell’arte Day 2021, three leading dell’arte artists, each in their own country (Christina Coltelli – Italy, Didi Hopkins – UK, Haim Abud – Israel) made lemonade out of their lemons and organized an online live international show: one Zoom platform hosted a “super-group” of 15 Commedia dell’arte artists from Italy, the UK, and Israel performing dialogues and monologues about plagues and pills, through the unique lens of Commedia dell’arte.

The show, performed live by 15 Italian, British and Israeli actors was broadcast live from the Hasimta Theater, accompanied by live traditional Italian music performed by an Italian musician. Pantalone, the MC, interacted with the online audience and moved the spotlight from scene to scene and from country to country.

Performed by: Italy – Chiara Daana, Enrico Bonavera, Alessio Sapienza Fabio Mangolini, Musician Nando Brusco, Cristina Colltelli;

UK – Didi Hopkins, Oliver Crik, Sarah Ratheram, Howard Gayton, Lee White;

Israel – Gilli Ivri, Lilach Tzur, Amir Lavie, Barak Gonen, Orit Peres

| Directed by: Haim Abud

| Artistic directors: Christina Coltelli (Italy), Didi Hopkins (UK), Haim Abud (Israel)

A special website specially designed for this year

The events in Israel were produced by the Scapino Ensemble, in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute in Tel Aviv, under the artistic direction of Haim Abud.

2022

This year, due to the ongoing pandemic, gatherings and celebrations were still not possible. In light of the situation and to mark International Commedia dell’Arte Day, the Scapino Ensemble initiated the production of a whimsical recorded interview program. The creation of this program was a collaborative effort between Scapino and the Italian Commedia dell’arte artist Cristina Coltelli. From the studio in Tel Aviv, specially set up for International Commedia dell’arte Day, various experts in their fields – Pantalone, Harlequin, Capitano, the Lovers, and of course, Dottore, were invited to discuss whether it is right and appropriate to celebrate Commedia dell’arte Day online?

Created by: Cristina Coltelli and the Scapino Ensemble | Produced by: Cristina Coltelli (Italy), Scapino Ensemble (Israel) | Direction and Artistic Management: Haim Abud | Performed by: Cristina Coltelli, Barak Gonen, Haim Abud, Efrat Cohen | Filming, Editing, and Graphic Design: Nimrod Tzin | Technical Interface and Digital Marketing: Natan Skop

The premiere was broadcast on Facebook, YouTube, and other platforms.

Independently produced by the Scapino Ensemble.

2023

This year, we were back to live venues and festivities took place over three days in three locations:

a masterclass at Goodman Acting School in Be’er Sheva, a celebratory 12th anniversary performance of “The Miser, Now What?” at Haifa’s Studio Theatre, and, to top it all off, a Saturday morning filled with activities for the whole family at Otef HaNagav Theatre in Ashkelon. Activities included two shows by the Scapino Ensemble – “How much Sky in the Sky” and “The Other-Siders,” a mask-making area for the entire family led by Einat Sanderovich – Scapino Ensemble’s mask designer, and a Commedia dell’arte mask acting workshop led by Hila Gonen, a member of the Scapino Ensemble.

see more photos

Production and Artistic Management: Haim Abud and the Scapino Ensemble in collaboration with Otef Ha’Negev Theater.

The Characters

Zanni

Status: Typically a lazy, crude and hungry servant. One of the two earliest characters in Commedia dell’arte (the other being “Magnifico,” the Venetian merchant who later evolved into Pantalone). As the genre developed, “Zanni” became a generic term for all servant characters, divided into two main types: the first Zanni, a sly and crafty servant originating from classical comedy’s ‘Conniving Slave’, and the second Zanni, a naive and simple servant, derived from classical comedy’s groveling slave.

Attire: Loose, light-colored, and dirty clothing (originally made from flour sacks), a tattered wide-brimmed hat, and a rope used as a belt, sometimes carrying a black bag or wooden spoon.

Character Origin: The underworld of Bergamo, where the lower class came from—porters, manual laborers, and other low-status professions.

Physical Characteristics: Despite the character’s depiction as heavy-set (a servant or manual laborer), Zanni can be highly agile and can move with ease, especially when on the run.

Mask: Generally dark-colored, with a low forehead, an elongated hook nose, and raised eyebrows revealing the expression, while the eyes themselves are small and round.

Prop: Carries a wooden spoon or a bag hanging from the belt.

Posture: Low center of gravity – knees slightly bent in a quasi-asymmetric stance, the weight mostly on one foot while the other is slightly angled. Bent back, hands with bent wrists resembling the grip of heavy bags. Even in a standing position, the legs are dynamic and often shift weight from one leg to the other. The head is also very dynamic, almost birdlike. When he sleeps standing up, one leg is raised pelvis-high, and the knee is straight, while the head moves up and down in accordance with his loud snoring.

Stride: Sideways steps with slightly bent wrists and hands stretched forward, nose leading, and the head swaying from side to side according to the leading foot. When escaping, rapid steps, hand opposite to leading foot. The legs lead the movement as the rest of the body is slightly tilted backwards.

Speech: Fast and sharp, using slang and everyday language.

Animal: Mule.

Relationships: Pantalone’s servant, and sometimes serves Capitano.

Audience Interaction: Directly addresses the audience, sharing all his thoughts, troubles, and joys with them.

Character Traits: Slow-witted and always hungry, lazy and capable of dozing off while standing. His faulty speech and lack of understanding of his master’s instructions lead to comedic situations. As the character evolved into two types of Zanni, the first was cunning and resourceful, while the second was innocent and simple.

Lazzi:

- The fly: Harlequin’s classic lazzo, where he tries to catch a fly to prepare a royal feast.

- Monologue accompanied by comedic pantomime describing his immense hunger and what he would be willing to eat in fantasy. The monologue usually ends with tears when he realizes he ate air.

- Dressing up as women or as doctors/pharmacists.

- Various acrobatic exercises.

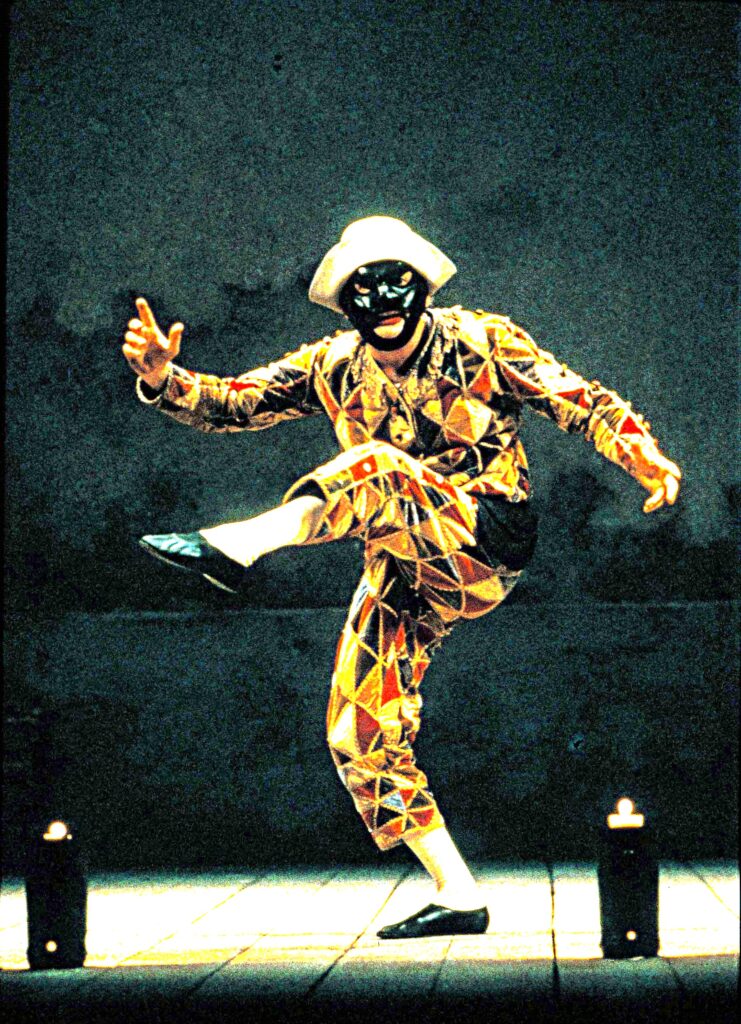

Arlecchino

Status: Servant. Initially portrayed as innocent and simple, but as the genre evolved, especially in France, Harlequin grew increasingly cunning and resourceful, a mischievous jester of sorts.

Attire: Initially characterized by loose, light-colored, and tattered clothing with stains in various colors and a belt with a slapstick attached. As the character evolved, mainly in France, the costume shifted to the classical harlequin diamond-patterned attire, which was more fitted to the actor’s body, emphasizing the character’s movement and body language, as well as his frequent use of pantomime.

Character Origin: The underworld of Bergamo, where the lower class came from—porters, manual laborers, and other low-status professions.

Physical Characteristics: Agile, bouncy, acrobatic and light on his feet.

Mask: Generally dark-colored, with a low forehead, high cheekbones, a small button nose, a little bump, reminiscent of a pimple, on the side of the forehead.

Prop: A slapstick – two thin wooden rods separated by a handle, creating a sound of a punch or a slap when struck. This prop gave its name to the popular genre of slapstick comedy prevalent on stage and screen.

Posture: Legs in a quasi-asymmetric stance, one foot bearing most of the weight while the other is slightly tilted. An open, leading chest. Hands with bent wrists placed near the belt or on both sides of the waist. Even in a standing position, the legs are dynamic and often shift weight from one leg to the other.

Stride: Fast, with small and light steps, chest leading, and the head swaying from side to side in accordance with the leading foot. It can also be slow and graceful when trying to sneak quietly.

Speech: Fast and sharp, using simple and everyday language. Can adapt to a higher language but is often filled with malapropisms as per his relevant scheme.

Animal: Cat and monkey.

Relationships: Serves Pantalone or one of the young lovers. Sometimes serves Capitano. Woos Colombina.

Audience Interaction: Directly addresses the audience, sharing all thoughts, troubles, joys, and schemes with them.

Character Traits: Good-hearted and hungry. Always advocates for love and a warm loaf of bread. Sometimes, due to a lack of understanding and clumsy interpretation, he reaches the most brilliant and subversive conclusions. His lack of understanding of his master’s instructions leads to comedic situations. As the character evolved in France, he became increasingly clever and cunning, and despite his position as a servant, he can outsmart his masters and achieve his goals. Harlequin combines folksy simplicity, vulgarity, ruggedness and cheekiness with wit, kindness, and charm. He woos Colombina, his “partner in crime,” and is always hungry.

Lazzi:

- The fly: Harlequin’s classic lazzo, where he tries to catch a fly to prepare a royal feast.

- Monologue accompanied by comedic pantomime describing his immense hunger and what he would be willing to eat in fantasy. The monologue usually ends with tears when he realizes he ate air.

- Dressing up as women or as doctors/pharmacists.

- Various acrobatic exercises.

Dottore

Status: A doctor of everything, boasting numerous academic degrees, but lacking real knowledge in any of these subjects. Head of the family but can also be a bachelor/widower (and if married, likely a cuckold, possibly father to one of the lovers). Typically accompanied by an assistant/pharmacist who carries out his bizarre instructions.

Attire: Black robe, large collar, may wear a flat academic hat or a period doctor’s hat.

Character Origin: Bologna, Italy’s academic center.

Physical Characteristics: Plump, large, and indulgent.

Mask: Covers only the nose and forehead (to enhance the effect of the indulgence, cheeks may be red with alcohol or fat). Some theories suggest that the mask originated from eyeglasses, as a symbol of academic status.

Prop: Book/white handkerchief.

Posture: Weight shifted backward, leading belly. Makes lots of large gestures with his hands.

Stride: Fast with small steps, can be slow when thinking/lecturing. The head moves in quick staccato movements (bird-like).

Speech: High academic language, seasoned with Latin/Gibberish English. Speech impediment – a lisp, etc.

Animal: Pig.

Relationships: Neighbor/friend/enemy of Pantalone, usually Harlequin’s master, and sometimes the father of one of the lovers.

Audience Interaction: Only when lecturing or boasting about his academic achievements.

Character Traits: Knows everything. Very verbal. Gluttonous. Older. Full of self-satisfaction. Greedy. His long and elaborate monologues bore the other characters until they fall asleep standing. A balloon filled with hot air. Cannot complete a sentence without a throwing in a bit of Latin.

Lazzi:

- Persuades a healthy person that they are sick.

- Diagnoses all the other characters while talking to them.

- During medical treatments, he never soils his hands, and his assistant does everything (fear of blood, etc.).

- Quotes scientific studies.

- Describes the obvious as his new invention.

- His treatment tools are often scary or comical, extreme.

Lélio

Status: In love. Usually the ward/biological son of Pantalone or Dottore. From a high social status. Background in higher education.

Character Traits: Dandy. Spoiled. A gentle soul. Dramatic. Emotional. When finally meeting his love interest, he is tongue-tied, and relies on his servants to communicate with her. Certain that everything revolves around him (in that sense – selfish). Not an ounce of malice/lack of integrity in him. Innocent. Direct. Passionate. Dreamy. Poetic. Often lives in a world of his own.

In most plays, the lovers are critical to the plot as everything unfolds as a result of the resistance to their affair and their aspiration to fulfill it.

Attire: Dolled up/en par with the latest fashion. Sometimes wears feminine colors. Character Origin: During the Renaissance, the aristocratic class was accustomed to watching shows based on classical Roman period texts, performed by amateur student actors.

Physical Characteristics: Young, elegant, delicate (borderline feminine ballet dancer), refined and attractive.

Mask: To reduce the grotesque level of the character and bring it closer to the classical image of physical perfection, lovers played without masks from the moment women were allowed on stage. Until then, female roles were played by men and the lovers wore masks (to create unity between the lovers). This mask was refined and closest to the definition of beauty in the classical period (close to the neutral mask of today). Once the masks were removed, they were replaced with heavy makeup.

Prop: Handkerchief/flower/mirror/poetry book.

Posture: Minimal contact with the ground. Usually, all the body weight rests on one foot, while the other is stretched to a point. Leading chest. Head raised (head in the stars). Hands never in a symmetrical position. Ballet positions.

Stride: Light, on tiptoes. Hands to the sides like wings. One hand points in the direction of movement. Feminine ballet-like walking. Exaggerated movements. When not in motion, he stands in a pose like a statue expressing his emotional state.

Speech: High language. Uses many metaphors and images. Musical/rhyming sentences.

Animal: Butterfly.

Relationships: In love with himself first, then in love with the feeling of being in love.

Finally, in love with his partner. When he meets his beloved, he is sometimes too excited to communicate. Master to a servant who assists him. The lovers accommodate their parents’ sanctions but, at the same time, turn to their servants who help them communicate with their beloved.

Audience Interaction: Aware of the audience’s presence and gaze. Sometimes directly addresses the audience when describing his love or uses the audience as an intermediary when too embarrassed to express his love in her presence.

Lazzi:

- An emotional monologue describing his love, which can move him to unconsciousness. Poetic hymns full of images depicting their love.

- In response to compliments on his clothing (for example), he adds more compliments on the matter.

- As soon as the long-awaited rendezvous with his beloved arrives, he becomes nervous and flees.

Isabella

Isabella

סטטוס:מאוהבת. Usually a ward/biological child of Pantalone or Dottore. From a high social status. Background in higher education.

Characteristics: Dandy. Spoiled. A gentle soul. Dramatic. Emotional. When finally meeting her love interest, she is tongue-tied, and relies on her servants to communicate with him. Certain that everything revolves around her (in that sense – selfish). Not an ounce of malice/lack of integrity in her. Innocent. Direct. Passionate. Dreamy. Poetic. Often lives in a world of her own. In relation to Lélio, she is more emotional, passionate, and energetic.

In most plays, the lovers are critical to the plot as everything unfolds as a result of the resistance to their affair and their aspiration to fulfill it.

Attire: Classic Renaissance-style muslin dresses/elegant and refined according to the latest fashion. Wears pearl/gold necklaces.

Character origin: During the Renaissance, the aristocratic class was accustomed to watching shows based on classical Roman period texts, performed by amateur student actors. Isabella Andreini of the Famous Gelosi Commedia dell’arte troupe was considered its highly gifted leading actress.

Physical traits: Young. Attractive.

Mask: When men portrayed her, the masks were the most refined and closest to the definition of beauty in the classical period (close to the neutral mask of today). When women stepped on stage, no mask was used. In a later period, appeared Venetian status masks (eye masks with feathers).

Prop: Flower/handkerchief/fan/mirror/poetry book.

Posture: Minimal contact with the ground. Usually, all the body weight rests on one foot, while the other is stretched to a point. Leading chest. Head raised (head in the stars). Hands never in a symmetrical position. Ballet positions.

Stride: Light, on tiptoes. Hands to the sides like wings. One hand points in the direction of movement. Feminine ballet-like walking. Exaggerated movements. When not in motion, she stands in a pose like a statue expressing her emotional state.

Speech: High language. Uses many metaphors and images. Musical/rhyming sentences.

Animal: Butterfly/Humming bird

Relationships: In love with herself first, then in love with the feeling of being in love. Finally, in love with her partner. When she meets his beloved, she is sometimes too excited to communicate. Mistress to a servant who assists her. The lovers accommodate their parents’ sanctions but, at the same time, turn to their servants who help them communicate with their beloved.

Audience Interaction: Aware of the audience’s presence and gaze. but does not address the audience directly. Sometimes directly addresses the audience when describing her love or uses the audience as an intermediary when too embarrassed to express her love in his presence.

Lazzi:

- When in an emotionally tense state, goes into the “passing out monologue”.

- Extreme dramatic emotional changes.

- Becomes hysterical and loses all sense of proportion when not getting what she wants.

Important note: All female roles developed from Isabella. Vittoria and Columbina are quite similar, but there are still some differences between them.

Pantalone

Status: High-ranking. Merchant. Employer, parent, guardian, his great fortune gives him control over everyone around him.

Plot Necessity: Typically, Pantalone is the blocking character. His opposition to the young lovers’ marriage creates the conflict that triggers the plot.

Character traits: Greedy, stingy, sly, neurotic, hypochondriac, dirty old man. Quick to enter extreme emotional states.

Origin: Venice, the harbor city of trade.

Attire: Red base (colors of the Venice flag), including tight-fitting trousers (from foot to knee) and widening breeches (adding a comic element). Option for an open black cape. In later periods, the colors varied, but the red always remains. Footwear: Gondolier shoes.

Physical traits: Bent, hunched (low pelvis and an arch in the back from tucking in his chest). Usually thin and short. A thin beard is optional, emphasizing his sharp features.

Mask: Elongated, hooked nose, sometimes with eyebrows, rarely a mustache. Age wrinkles.

Prop: Money pouch (sometimes hanging from a belt), pocket watch, handkerchief.

Posture: Rounded back (of an older man), guarding the money in his pocket. Feet close together in a 45-degree turnout. Feet close together. Knees turned outward. Dynamic and expressive hands.

Stride: Tiny, quick steps. Fast and sharp bird-like head movements. Dynamic limbs (hands, feet, and head)/ Walking with his hands folded behind his back.

Speech: High-pitched and nasal tone. Elevated language.

Animal: Turkey.

Relationships: Cruel to his servants, narrow-minded and harbors a desire for control over his children, sometimes kisses up to Dottore, aggressive towards Capitano but equally capable of “falling for” his made-up heroic tales. Horny. Slobbers all over Columbina and the female servants.

Relation to the audience: The audience is a partner for him. A nearly exclusive accomplice in all his thoughts, schemes, and desires.

Lazzi:

- The Beetle.

- Two Pantalones meet.

- Toothaches.

Pulcinella

Status: From a low social status, could also have a profession. Comes from Naples.

Character traits: A highly gifted mimic, a trait that helps him change identities according to his agenda. A fool pretending to be wise and vice versa. Violent, human life is worthless to him. Loves food, drink, and sex, but will never work for any of it. Sly and cunning.

Plot Necessity: He can sometimes be the messenger of the blocking character (Pantalone/Dottore), sometimes acting on his own (Tartuffe), on rare occasions he is not crucial to the plot’s development, instead providing comedic elements and positions.

Attire: A long white robe, elongated hat, his attire is often oversized.

Character origin: Evolved from the groveling Roman slave.

Physical traits: He has a hunchback that causes a certain curvature of the body leaning forward.

Mask: Wide and hooked nose, wrinkles on the forehead.

Prop: Money pouch/bottle/baton.

Posture: Weight always on one foot (Always ready to move). His nody changes according to the situation given.

Stride: Small steps that can suddenly become large and fast.

Speech: Loud voice.

Animal: Snake.

Lazzi:

- Advertises himself as a doctor, but his treatments always end up harming patients.

- Pretends to be blind/deaf/mute to elicit handouts.

Vittoria

Status:

Comes from a high social standing, but due to circumstances, her status declines.

Attire:

A simple, colorful dress, reminiscent of gypsy clothes or similar to those of Isabella.

Character origin:

The commedia erudita.

Physical traits:

Beautiful and attractive. Young.

Mask:

Similar to that of the lovers yet less pure and chaste than the female lover, more experienced with heartache.

Prop:

(Similar to Isabella)

Posture:

(Similar to Isabella)

Stride:

(Similar to Isabella)

Speech:

Similar to Isabella:

Animal:

(Similar to Isabella)

Relationships:

(Similar to Isabella)

Plot Necessity: The lovers are critical to the plot as everything unfolds as a result of the resistance to their affair and their aspiration to fulfill it.

Characteristics:

Similar to Isabella but differs from her in her experience with heartache and her declining social status.

Lazzi:

(Similar to Isabella)

Capitano

The Stranger – usually a non-local resident (originally Spanish) hired for protection services. His name is long, consisting of multiple absurd titles or a multitude of surnames recited rapidly and consecutively, with the last name expressed with particular gravitas and emphasis – “…my name is Captain Patricio, son of Maurizio Salvador Theodore Jose Consecutivo of Guadalajara the Second!”

He brags of heroic deeds and often delves into his romantic escapades – “…I am the hero of heroes, the brave among the brave, the mover of mountains and rivers, breaking the hearts of endless young maidens, an expert in Kung Fu, karate, and ballroom dancing!

He is inseparable from his sword (cane) which is essentially an extension of his body – strong and tough, with a “muscular” posture. Each of his poses is a sculpture of heroism and indomitable spirit.

Texts

Here you can download full texts of original Scapino Ensemble plays for free!

- The performance of the plays does not require the use of masks.

- All our plays are performed with masks; therefore, the plays are written to allow each actor to portray multiple characters. Hence the varying number of actors in each show.

- The use of texts is for non-profit educational purposes only.

A Minister’s Honor

A satire for adults in the style of Commedia dell’arte. The play is inspired by Plautus’ “Miles Gloriosus” and is a satirical farce poking fun at government, power games, personal agendas, and ego all of which are present in the plot and on the stage, typical of the Commedia dell’arte tradition.

Play Barak Gonen

Summary Somewhere within the Roman Empire, the Minister of War in times of peace aspires to become the next emperor. To achieve this goal, he must bring a child into the world within the coming year. This task is far from simple, as he faces his cunning and conniving assistant, a greedy hotel owner, a failed actress, and a young couple from an underdeveloped city. In these turbulent times, as we are exposed to governmental farces from all sides, watching the play offers a fresh perspective on the real-life circus we are all living in.

Number of Actors 5-7 Actors.

Lélio’s Treasure

A children’s play In the style of Commedia dell’arte, inspired by a 17th-century Italian folktale, featuring the characters of the clever Arlecchino, the miserly Pantalone, the slow-witted servant Turtuglia, and the lovestruck Lelio and Isabella.

Play Barak Gonen

Summary Lelio, a poor young man whose father left him nothing but a hungry servant, and Isabella are in love and wish to marry. Pantalone, Isabella’s father, who is obsessed with money and honor, completely rejects the intended match, dismisses Lelio, and plans to find a suitor for his daughter who will be of high rank and wealthy—a duke, prince, or rich king. To prevent a meeting between Lelio and Isabella, Pantalone assigns Turtuglia, his clumsy servant, to guard his home. Arlecchino, wanting to help his unfortunate master, devises a scheme: Lelio will disguise himself as a prince from a foreign land (a non-existent country abroad), searching for a wife to marry and make her a princess of this foreign land. Through Arlecchino, who is disguised as the prince’s page, Pantalone becomes excited about the opportunity that has come his way—money and noble status from the kingdom of the foreign land—approves the marriage, and even receives the coveted title of nobility at the wedding’s conclusion.

Number of Actors 4-5

The Other-siders

A children’s play In rhymes in the style of Commedia dell’arte, combining physical humor, clowning, pantomime, and music, reinforcing the message that ‘one should not cast aspersions on anyone without examining their character.’

Play Barak Gonen

Summary In the city of “Adomania,” everything is red, and there is no room for any other color. So, what will the mayor, Baron Redamemnon, do with all the spots appearing on his body? What will his daughter, Redmonella, do when she falls in love with Bluelue from “Blunea” – the reds’ rival city? Will the residents of Redville truly get to know the “other-siders”?

Number of actors 5-6

The Miser, Where Now?

A satirical comedy for youth and adults In the style of Commedia dell’arte, the play examines the role of theater in today’s cultural life and its relationship to tradition and its audience. All this while emphasizing the dialogue between Molière and the style of Commedia dell’arte, as well as between the classical language and style of the original play and the modern language and contemporary Israeli culture.

Play Barak Gonen

Summary “There’s a problem! The play isn’t working; we must make changes!” Thus declares the producer and director of the Commedia dell’arte troupe during the dress rehearsal, on the eve of the premiere of Molière’s play “The Miser.” From here begins a power struggle between the producer-director, who wants to create a commercial production and avoid another commercial failure, and the lead actor, portraying ‘The Miser,’ who is doing everything in his power to preserve the tradition of classical theater as it should be.

Number of Actors 3-8

A Cinderella Story

A children’s play in the style of Commedia dell’arte—featuring physical humor, clowning, puppetry, and music—and reinforcing the message that ‘with willpower, imagination, and faith, the sky is not the limit!’

Play Haim Abud and Avia Ohayon

Summary Ms. Pantalone’s theater troupe arrives in town to perform the tale of ‘Cinderella.’ The stage is all set, the audience is in their seats, but lo and behold, the lead actress playing Cinderella – has disappeared. The desperate Mrs. Pantalone decides to call off the show. Her dedicated stage workers, Columbina and Baguettino do their best to reverse the decision. They find a way to join forces, and with the help of imagination, willpower, and the charms of Arlecchina the fairy.

Number of Actors 3-6

Romeo and Juliet – the Verona Version

A completely free comedic adaptation of Shakespeare’s play “Romeo and Juliet.” A multi-participant play specially adapted for highschool theater programs.

Play Barak Gonen

Click here to download the text of “Romeo and Juliet: The Verona Version.”

Recommended Videos and Articles:

In our years of learning and teaching, we have encountered more than a few students and fellow artists interested in expanding their knowledge in the field of pantomime, masks, Commedia dell’arte, and physical theater.

In this section, you will find various articles and videos (catalogued by subject), and additional links to help broaden your knowledge:

Selected Bibliography:

- “From Carnival to Theatre: Patterns and Chaos in Commedia dell’arte,” Ahuva Belkin.

- “Commedia dell’arte from Harlequin to the Present,” Jacob Meshan Montfiori.

- Article: “Isabella” by Shai Bar-Yaakov. Be’er Sheva Theatre website.

- The Italian Comedy, Pierre Louis Duchartre

- Commedia Dell’Arte: An Actor’s Handbook, John Rudlin

- The Comic Mask in the Commedia dell’Arte: Actor Training, Improvisation, and the Poetics of Survival, Antonio Fava

- Lazzi: The Comic Routines of the Commedia dell’Arte, Mel Gordon

Videos:

- Scapino Ensemble’s YouTube Channel (including full-length performances)

- Prof. Yoram Boker’s YouTube Channel

- Dr. Chiara D’Anna’s YouTube Channel (instructional videos on various Commedia Dell’arte characters)

- Commedia dell’arte by Didi Hopkins

- “The Servant of Two Masters” – the legendary production directed by Giorgio Strehler

- Captain Fracasse 1990

- Etienne Decroux – the father of modern pantomime.

- Marcel Marceau – the messenger of the message and the master of masters. Marceau speaks about pantomime as a performance art. Classic stage works of Marcel:

- “The Importance of Mimicry in Pantomime” by Edward Grigorian.

- “White Pantomime” by MiMo Chispa.

- “Movement Combined with Contemporary Pantomime” by Tyson Eberly.

- – “Modern Clowning with Pantomime” by Patrick Sébastien.

- – Contemporary pantomime by Michel Courtemanche.

- – Commedia dell’arte and Pantomime – the winning combination!